As mentioned before, I said I was going to start a series of interviews with some of the great artists I know. Here is the first one with watercolor artist Paul Pitsker.

I met Paul when I was a member of the Los Angeles Art Association, also known as Gallery 825, in the early 2000s. I met a lot of artists when I was in that group and I have to say that it was an excellent springboard for getting my feet wet in the Los Angeles art scene in general. I learned a lot and was able to understand how to navigate the art network on a more professional level. The more involved you get in that organization, the more of an asset it is for you as an artist.

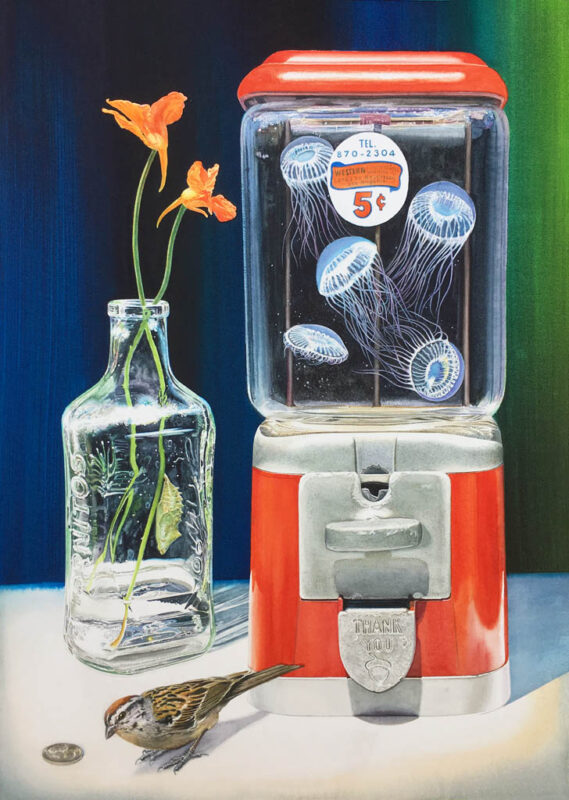

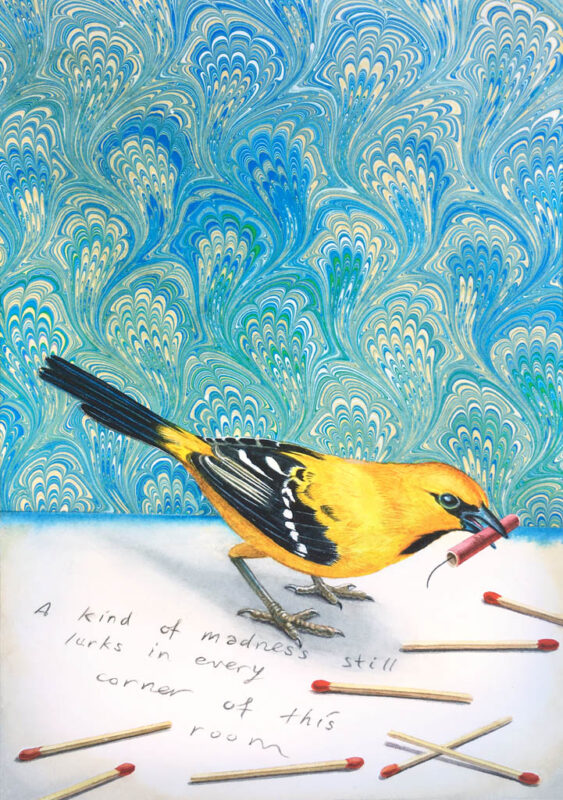

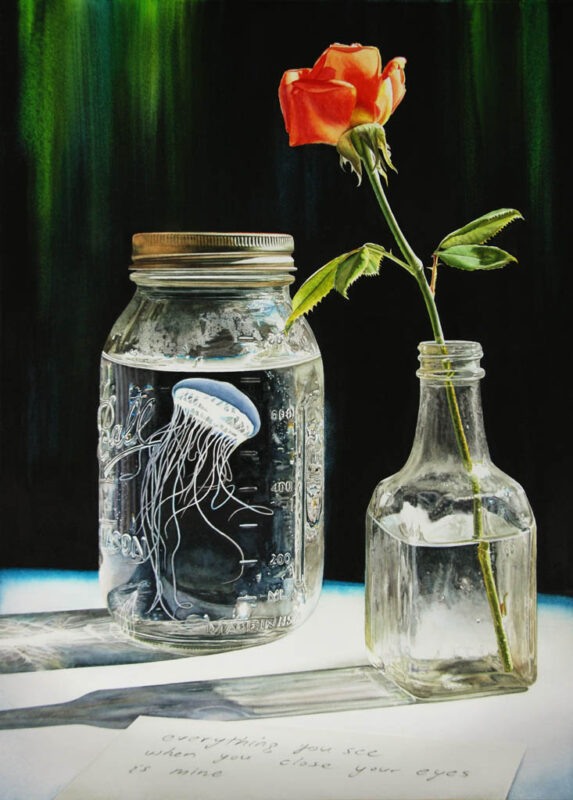

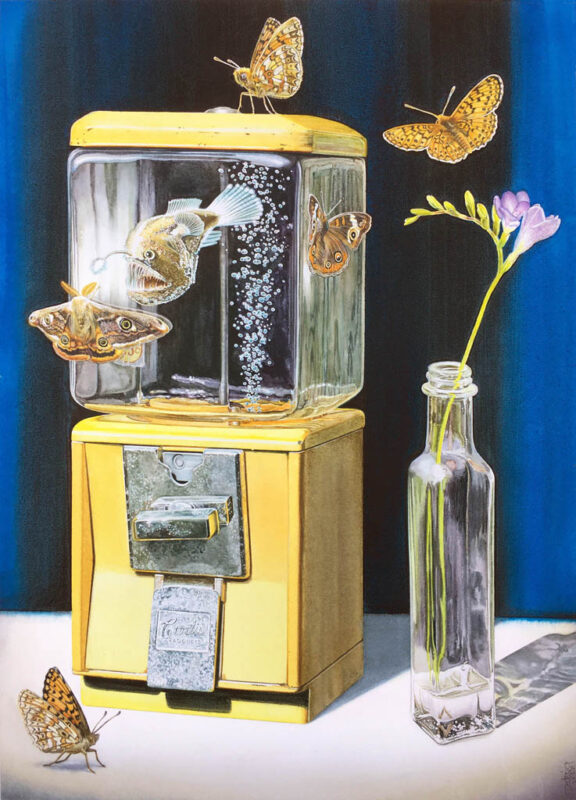

Paul isn’t just an amazing watercolor artist. He’s a surrealist. It’s what makes his work so appealing and so cool, and it’s why I like it. It goes with his personality, if you knew him like I do. His strange ideas are always present in his work—even before he did strictly watercolors, his ideas were always deadpan funny. His humor reminds me a bit of Steven Wright’s comedy. Yet, his paintings have such a beautiful, natural aesthetic. They are rendered rather perfectly both in color and draftsmanship. Really gorgeous works of art.

Paul is a big fan of the High Desert, but lives in Santa Monica CA with his wife and two kids. He is a trained musician and a kind of computer programmer genius, but not a dork. He’s one of the smartest people I know and is good peoples. He mostly paints in a tiny little shack in his backyard where only he can fit inside, even though he’s one of the tallest people I know. He wears a hat too because he doesn’t care what you think.

Okay, now for the Q & A.

Me: Did you go to art school or are you self-taught? How or where would you say you’ve learned the most?

Paul: I drew obsessively for hours a day when I was young, but all the adults in my life were dim on the idea of art as a career. So, I focused on other interests and ended up getting my bachelor’s degree in mathematics. By my final year in school, I realized it was a mistake and that art was my real passion, so I took my first ever studio art class – Beginning Drawing – and the teacher told me I should become an artist. This was the first time that anyone had ever said that to me, so I was like “Okay, I’ll do it.” She also added “if you think you have the stamina,” which I only came to appreciate much later. I tried the self-teaching approach for years, and then I finally took more drawing courses and a watercolor class and was accepted into a mentorship at Santa Monica College in my late 20s. That’s where I learned the most, especially in the mentor program, where my critiques with faculty member Ronn Davis often turned into long, free-wheeling and insightful conversations about art and life that ran hours past our allotted time.

Me: Before you focused strictly on watercolor and realism, can you tell us about some of the other mixed media you were working in and the significance behind some of it?

Paul: I went through an experimental period early on, where I tried various media and experimented with making images on a variety of surfaces. I incorporated photography into painting with polaroid transfers combined with watercolor, or with xerographic transfers onto acrylic paint sanded smooth, or by simply painting over collaged photos. These artworks were all pretty murky looking — I now call this my Brown Period — but I was more concerned about concept at the time. My thinking was that if the best art was about communicating important yet elusive truths that resist expression in ordinary language, then my work would be about trying and failing to achieve that ideal. It was to be an art that celebrated and elevated the mundane and comically fell on its own face in the process. Originally the images were multimedia composites of banal Americana (pop tarts, RVs, macaroni and cheese, toasters, etc.) combined with textual wordplay. Then I did a series of surreal oil paintings of figures stuck midway through strange transformations that left them a writhing mess of mismatched arms, legs, wings, and feathers. I think those were the paintings I was making around the time I met you way back when. All of it was about alienation and longing and thwarted desire, in my mind, but I think most of the resulting paintings were a little too weird and obtuse, and yet not quite weird enough to be successful.

Me: What made you transition to only watercolor, and specifically flowers, animals, and bugs in precarious situations?

Paul: One of my best and funniest friends died unexpectedly in 2004, which got me thinking with particular intensity about the fragility of life and the inevitability of difficulty and darkness, and so I began painting fragile and vulnerable subjects in watercolor, which as a medium has a reputation for being delicate and unforgiving. The membranous insect wings and translucent petals and glassware in my setups seemed perfect for a mostly transparent medium, as a practical matter, and I found the inherent prettiness of these subjects was a way to draw people in while softening the tragicomic existential payload that I had in mind, which is the realization that we are all subject to fate and forces beyond our control and perhaps it’s okay to laugh about that. And the level of empathy an average person feels for a pot of tulips on a lit stove or a bug on a live electrical wire is manageable – the situation can be funny in a way that it would not be if the subject were, say, a mouse or a kitten in danger. You might remember the Voight-Kampff test in “Blade Runner” that was used to detect androids, who were incapable of a normal empathetic response… It worked, but it also unleashed a deadly violent reaction when the questions got too personal. So, I want my paintings to test whether you are an android pretending to be human, but without pissing you off in that way.

Me: Have you ever had a significant art epiphany whether philosophical or applicable? If so, are you willing to share it, even if it later faded away?

Paul: This is somewhat corny, but I had a major epiphany when I saw Van Gogh’s “Irises” for the first time. We lived in the woods in New England when I was young, and I was a teenager in southernmost Orange County, which was a cultural desert back then, so I was underexposed to visual art while growing up. But I made it up to LACMA in 1984 for a big show of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist landscapes (“A Day in the Country”), and when I came across Van Gogh’s painting, I swear the ceiling above me opened, the clouds parted, and beams of heavenly light shown down as I walked towards it in awe. I had never had such a strong physical and emotional reaction to an artwork until then, and I was convinced my life would never be the same. But the only thing that really changed in the short term was that I signed up for a drawing class and started dabbling for the first time with oil paint… It was too late to change the course of my education, but at least the seed of something else was planted.

Me: Who were your very first artistic influences? Who are your current ones?

Paul: Well, I had an intense infatuation in my early twenties with Van Gogh and his contemporaries after the “Irises” encounter I mentioned — Gauguin, Bernard, and Toulouse-Lautrec were among my other favorites at that time. And then I became intrigued with symbolist painters like Fernand Khnopff, Arnold Böcklin, and Odilon Redon. It was the atmosphere of disquiet in their work that I could relate to as an entitled but tortured twenty-something. I traveled to New York City and then around Europe for four and a half months after college, looking at art and living cheaply, sleeping on trains or outdoors or staying with friends to keep the journey going as long as I could. In Berlin, Gerhardt Richter was a revelation, though I liked his photo-based paintings better than the newer squeegee stuff. There was also a photo by Mike and Doug Starn that I saw somewhere years later that really stuck with me, an extreme close-up of a white moth with otherworldly black eyes. That image was still on my mind when I began painting insects in 2005 – one of my first large watercolors that year was of a white moth with owlish eyes surrounded by snowflakes. But other than the one moth, none of these artists’ works have any obvious similarities to what I do now. And my influences nowadays are mostly from the non-art world… There are a ton of artists I admire, but Gary Larson (the cartoonist) and Jack Handy (the writer and humorist) might be bigger influences on the content of my work now than any visual artists I can think of.

Me: When you spend any time looking at other people’s art, how do you view it—through Instagram, magazines? family members, Internet, museums, galleries?

Paul: These days my art explorations are all on the internet. I loved going to gallery openings back when we lived in a world where that was still possible, but those outings seem like a distant memory now. And I visited a lot of museums and galleries when traveling, especially in recent years. But for now, it’s all happening on a small screen. Instagram is a mixed bag. I’m really happy to have connected with so many fellow artists and watercolor fans from all over the world, and some of the work I see is amazing, so it’s net positive. But there is also a ton of amateur and student art you wade through to find anything noteworthy. And the images that constitute the “top posts” on Instagram are rarely top in quality, in my opinion – a high ranking might just mean an artist has mastered the art of feeding the Instagram beast what it wants, while looking young and attractive in the process.

Me: Do you ever get envious of other people’s work? If so, can we know whose?

Paul: Yes, I get envious all the time! Rebecca Campbell is one of my favorite painters anywhere. Her “Sugar House” depicts a bee hovering in a jar placed in a field of grass, all painted with delicious brushstrokes and flawless blending. It looks like something I might have done if I really knew how to paint with oils. All her early work is simply stunning.

Alexis Rockman is another favorite. Sometimes I think about what it would take for me to create large, ambitious oil paintings like his with complex environmental themes, and then I lie down and take a nap.

Alyssa Monks is also off the charts amazing, though I think her paintings might seem creepily voyeuristic if they were done instead by a male artist. I am envious of her talent in any case.

Me: How does an idea begin for you and how does it transform into a finished piece? Can you share some of your process?

Paul: Often an idea begins with me noticing something that’s been lying around the house forever, like an old toaster or a vintage bottle or some plastic mermaid cocktail charms or whatever. Or sometimes the starting point is some text that I scribbled in one of my sketchbooks. I take a lot of photos of birds visiting our feeder and insects in the yard as well. For the more exotic critters in my current show, like the octopuses or the anglerfish, I combined multiple images from the internet and then redrew many of their body parts digitally to change the angles, fit them into bottles, etc. Watercolor seems to reward careful planning, so I typically create a complete study for an entire piece in Photoshop and/or Procreate that is a collage of several manipulated photos combined with digital drawing. An obvious question is why not just hit the print button at that point and let the digital study be the finished work, which would be way less labor-intensive… The answer is that the digital images look dead to me – it’s the process of rendering that same image in watercolor, with all the unexpected twists and turns that arise from the unpredictability of that medium that give it the spark of life. So, in a way, my primary medium is photography, and I’m just the world’s slowest printer.

Me: Do you use any kind of magnifier, or do you have excellent eyesight?

Paul: I have terrible eyesight these days, so I usually paint with strong reading glasses on while holding a magnifying glass in one hand.

Me: What size range do you like working in, and is there a reason you like working in those sizes?

Paul: The painted areas of my watercolors range from about 8 x 6 inches up to 25 x 18 inches. The upper limit is determined by the size of a standard full sheet of watercolor paper, which is 30 x 22 inches, with some loss to taping during the stretching process and some paper left unpainted at the edges to have a clean margin. There are larger paper sizes, of course, and I have a roll of Arches paper I thought I would use to work bigger, but that rolled paper is noticeably inferior to the individual sheets by the same manufacturer. I’m not sure why that is, but the framing difficulty for works on paper also increases geometrically with size, so I’m comfortable in this size range. My smaller sizes are for ideas that feel more intimate, and these smaller works also provide options for collectors on a budget. When I get back to working in other media again, I’d like to do some larger paintings, but since my studio is small and kind of jam-packed, I don’t know when that’s going to happen.

Me: What kind of paper do you use? (Typically.)

Paul: Almost always Arches 140 lb. hot-press (smooth), or very occasionally, 300 lb. hot-press. For some of the pieces in my current show that have marbled watercolor backgrounds, I had to flex and then un-flex the paper as I lay it down on the marbling tray to pick up the pigment without air bubbles, so I couldn’t first stretch the paper on a stiff drawing board, which is my usual preparation to keep 140-lb. paper from rippling. So that was a case where 300 lb. hot-press was better. But I’ve found the 300-lb. paper is not as smooth, for some reason. And I like to work on the smoothest surface possible, so the final results are not so obviously watercolor-y.

Me: That’s my favorite paper too! Do you have future business-type goals for selling your art in galleries, commercially, for products, textiles, designing, prints, toys, originals, museums, the Whitney, or otherwise?

Paul: Selling art in galleries seems to be going well now, but I could still happily expand in that area. And I’m working on an idea for a book, but it’s early to say too much about it. As for other business opportunities, I’m not ruling anything out. These are difficult times for everyone and it’s good to be open-minded and think outside the box, even if it doesn’t come naturally.

Me: What would you tell your younger self when he was just starting on in art that you which she knew? Would you warn him, soothe him, both? What advice would you give him?

Paul: If I were talking to myself in my teens, I’d say remember when you used to draw on the floor as a kid for hours a day until your mother begged you to go outside, or when you’d ask to stay at your desk during recess in school just to have 30 minutes more drawing time? Stay true to your passion and don’t listen to what anyone says about how practical it is. And if I were talking to myself in my twenties, I would say to look for the sweet spots where your own interests and life experiences and natural abilities come together and don’t worry about what kind of art you think you should be making based on what you read or hear. I got a late start on my own art career and an even later start in finding my own voice because I was too easily influenced by other people’s opinions.

Me: That’s great self-talk. Do you have any good, practical advice for other watercolor artists? Anything from masking, painting light to dark/dark to light, wet on wet, erasing pencil lines, you name it!?

Paul: Sure, here are some nuts-and-bolts suggestions for watercolorists… Stretch your paper – it makes a huge difference, not just by preventing rippling and curling but by making the paper surface more absorbent. Use the best quality tools and materials – sure, they’re more expensive but there’s minimal waste with watercolor because dried paint on your palette is re-usable. And good watercolor brushes can last for many decades – they don’t get stiff over time from dried paint in the ferrule like oil or acrylic brushes. And a full sheet of Arches is only about $7 if you buy in bulk, so you’re not saving much if you go cheap. Plus, paper is your most mission-critical material, so definitely don’t scrimp there. Plan your paintings so you know in advance where the white (unpainted) areas will be and defend these with your life! Use drafting tape for masking, never artists tape or regular masking tape. Try using staining pigments to get intense hues and darker darks… I think the problem with most amateur watercolors is insufficient tonal range, especially on the dark end. Try limiting your palette to just a few colors so you can get to know them well. I typically use just six colors: phthalo blue, phthalo green, quinacridone magenta, Winsor yellow, Payne’s gray, and lunar black. Use a hairdryer on low air, high heat setting for uniform drying and to prevent drying lines. Use a short-haired nylon bristle brush and clean water to correct mistakes or to soften hard edges. You can also scratch off paint with an X-Acto knife or fine-grit sandpaper, but learn to recognize when your paper is getting tired and stop before it really unravels. This is the best thing about watercolor for me, since I’m borderline obsessive-compulsive and have been known to labor on oil paintings for years. But with watercolor, the materials will turn on you viciously if you insist on carrying on too long. So that’s what I like most about it.

Me: That’s advice I will definitely consider myself. Thanks! And thank you for doing the Interview Paul!

Paul: Many thanks for your interest and for reading all that!

If you would like to see more of Paul Pitsker’s art, follow him on Instagram, or visit his website at PaulPitsker.com.

EDIT: I should also mention that Paul is having a solo show right now at George Billis Gallery in Los Angeles until January 16th, 2021.

Great interview!

Pitsker’s work is new to me, and I’m generally not much for contemporary surrealism, but I love these watercolors!

Thanks Ruth. I think he’s wonderful. Great to hear from you!